Marriage is fundamentally an exclusive bond based on trust and commitment. While Muslim law permits limited polygamy for men, marriage is generally seen as a union between one man and one woman. Engaging in sexual relations outside of marriage is regarded as a serious violation of trust and fidelity in all personal laws. Consequently, such conduct is recognized as grounds for divorce or judicial separation.

Under the Hindu Marriage Act of 1955 and the Special Marriage Act of 1954, the terminology used is not “adultery,” but rather that the respondent has engaged in “voluntary sexual intercourse with a person other than the spouse.”

For an act to be considered adultery, it must satisfy two key criteria:

- There must be sexual intercourse outside the marriage.

- This intercourse must be consensual.

Section 497 of the Indian Penal Code

Adultery – whoever has sexual intercourse with a person who is and whom he knows or has reason to believe to be the wife of another man, without the consent or connivance of that man, such sexual intercourse not amounting to the offence of rape, is guilty of the offence of adultery, and shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to five years, or with fine, or with both. In such case the wife shall not be punishable as an abettor.

Joseph Shine V Union Of India

Facts of the case

Joseph Shine, a non-resident Keralite, filed a public interest litigation under Article 32 of the Constitution, challenging the constitutionality of adultery as outlined in Section 497 of the IPC and Section 198(2) of the CrPC.

In his petition, he claimed that the law discriminates against men by holding them solely responsible for extramarital relationships while treating women as objects. He stated, “Married women are not a special case for the purpose of prosecution for adultery. They are not in any way situated differently than men.”

Furthermore, Mr. Shine argued that the law indirectly discriminates against women by reinforcing the mistaken notion that they are the property of men.

Issued raised

- Is Section 497 of the IPC (which makes adultery a criminal offense) constitutionally valid?

- Is Section 198(2) of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 violative of fundamental rights (Articles 14, 15, and 21)?

- Is Section 497 an excessive penal provision that needs to be decriminalized?

Arguments advanced by the petitioner

Section 497 of the IPC is prima facie unconstitutional as it discriminates against men, violating Articles 14, 15, and 21 of the Constitution of India. The law unjustly imposes liability solely on men for adultery, even though sexual intercourse generally occurs with the consent of both parties. This lack of justification contradicts the principles of equality. Landmark rulings such as Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India (1978), R.D. Shetty v. Airport Authority (1979), and E.P. Royappa v. State of Tamil Nadu (1974) reinforce the necessity of equal treatment under the law. Consequently, Section 497’s discriminatory nature undermines the fundamental tenets of justice and equality enshrined in the Constitution.

Section 497 of the IPC cannot be interpreted as a beneficial provision under Article 15(3) because it indirectly discriminates against women by upholding the mistaken belief that they are the property of men. This is illustrated by the fact that if a husband consents to his wife’s adultery, the act is no longer punishable under the law. Such reasoning constitutes institutionalized discrimination, which the Supreme Court addressed in Charu Khurana and Ors v. Union of India and Ors. (2015). This principle is also reflected in Frontiero v. Richardson (1973), emphasizing the need for equality and non-discrimination in legal statutes.

Arguments advanced by the respondent

The writ petition under Article 32 of the Constitution of India is likely to be dismissed at the outset, as Section 497 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860, is intended to support and protect the institution of marriage. This viewpoint was reinforced in Sowmithri Vishnu v. Union of India, where the court acknowledged the importance of the provision in maintaining marital integrity.

Striking down Section 497 and Section 198(2) of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, would effectively decriminalize adultery, which could undermine the sanctity of marriage and the overall social fabric. The government is already addressing concerns related to gender bias. The Supreme Court, in W. Kalyani v. State Tr. Insp. of Police & Anr (2012), emphasized the importance of tackling gender disparities within the legal system.

Judgment

A law that denies women the right to prosecute is inherently not gender-neutral. Under Section 497, a wife is unable to charge her husband with marital infidelity, making this provision ex facie discriminatory and a violation of Article 14. Section 497 cannot escape scrutiny under Article 14, which reveals any unreasonable, discriminatory, or arbitrary elements.

Article 15(3) of the Constitution allows the State to enact beneficial legislation for women and children, aimed at protecting and uplifting these groups. However, Section 497, which criminalizes adultery—typically a consensual act between adults—cannot be classified as beneficial legislation under Article 15(3).

The true objective of affirmative action is to empower women in socio-economic spheres. Legislation that removes women’s rights to prosecute cannot be considered “beneficial.”

While the right to privacy and personal liberty exists, it is not absolute; it is subject to reasonable restrictions when legitimate public interests are involved. Although the boundaries of personal liberty can be complex, they must accommodate public interest. The freedom to engage in consensual sexual relationships outside of marriage does not warrant protection under Article 21.

Conclusion

The law must adapt to reflect the changing ideas and ideologies within society. It should recognize societal transformations and align with emerging concepts and values. The interpretative process of law must respond to contemporary needs.

Equality before the law encompasses not only equal access but also equal exposure to legal protections. This principle was upheld by the five-judge bench of the Supreme Court, which declared Section 497 of the Indian Penal Code unconstitutional after 158 years of criminalizing adultery. However, the core rationale and true spirit of this ruling will take time to be fully integrated into the current social framework. Adultery can be grounds for divorce , but not a criminal offence.

📚 Explore More Legal Services at VantaLegal

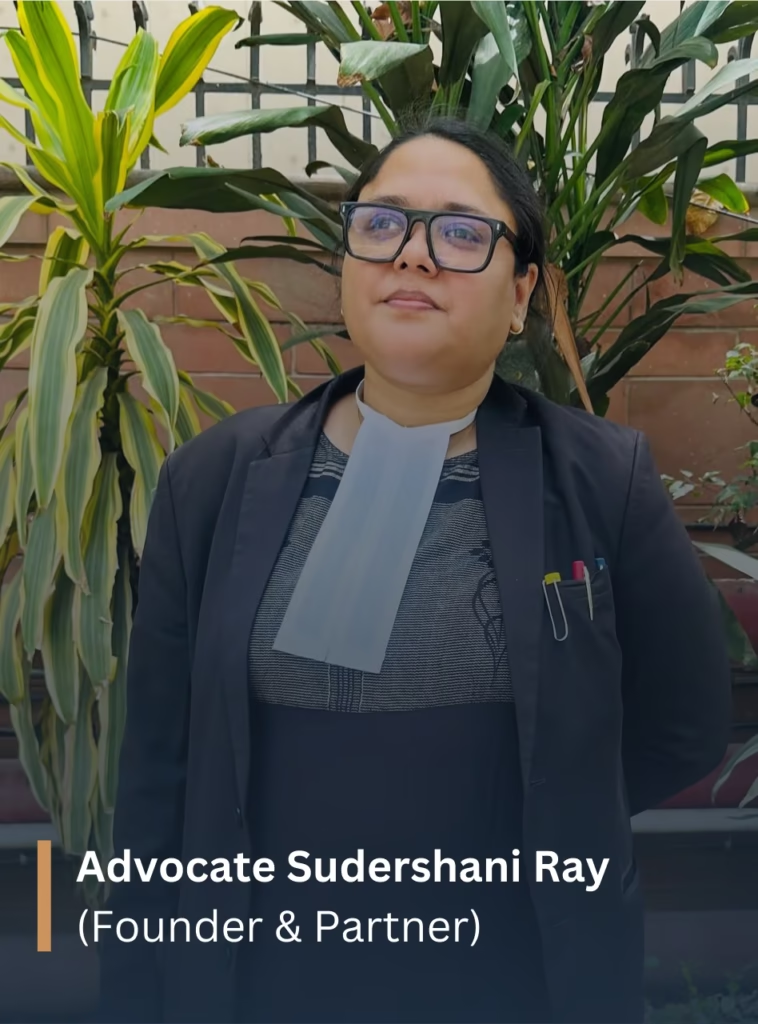

📞 Contact Vanta Legal | Advocate Sudarshani Ray

Have a legal question or need expert advice? Get in touch today.

📧 Email: vantalegalofficial@gmail.com

🔗 Contact Page: https://www.vantalegal.com/contact-us/